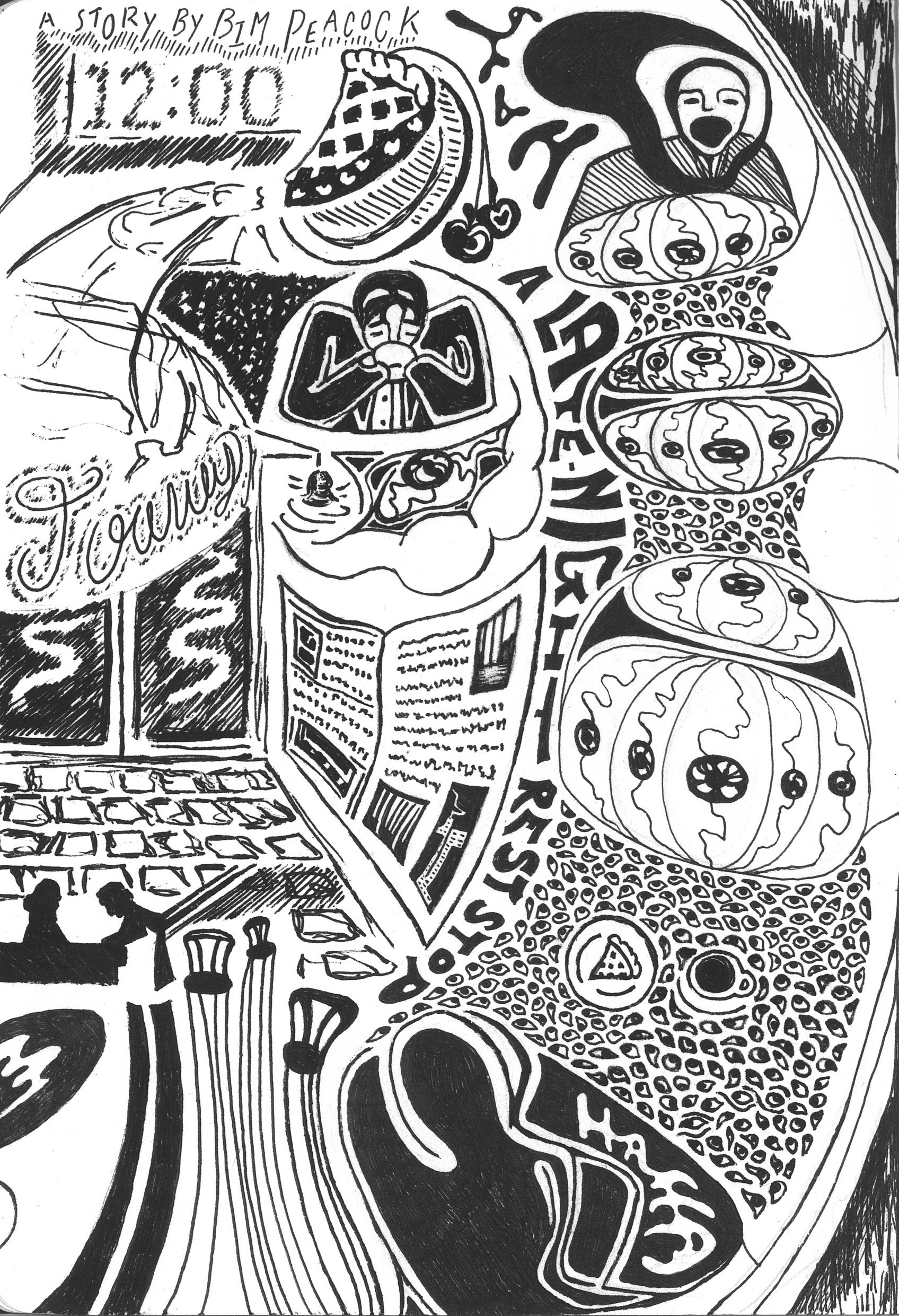

Everybody left. The Earth went quiet.

*Everything was supposed to be done with equipment. For decades, satellites and rovers explored, taking readings and transmitting them back to distant colonies. The first rover going quiet was unexpected, but explicable: the planet was still full of animals and antagonistic weather forces that could easily put paid to the best laid plans. And then a second blinked out of existence, and with a static screech, the satellites stopped talking. Once again, the world went quiet.

So they sent people. PhD students, actually; some straight into the fields of their once- theoretical research, and others are taken for their expertise and the chance of a year away

from overtime and paltry, late salaries. They send Mahira and Sel to the last nuclear reactor to erupt like a dormant volcano. This is where the first rover died. *RX-2041B sits listless and forever unmoving in the grass. Though there’s no sign of damage to its hull or inner machinery, it’s simply stopped working, and nothing Sel does can revive it. His fingers go still when the realisation hits, chest rising and falling with ragged breath, crouched over a lost companion. “It shouldn’t have died,” he says, both a statement of fact and an expression of mourning. RX-2041B is almost as old as Sel himself and spent its long life discovering things that were lost in the interplanetary move.

They call it Laika and bury it.

“Won’t it disturb the radiation in the soil?” Mahira had asked tentatively, but Sel had simply shrugged

“Don’t you think Laika deserves it?”

Before they finish the burial, they both throw three handfuls of dirt into the earth and Mahira apologises for its disturbance. When the grave is finished and marked with a pattern of stones and twigs, she bows her head. “To Allah we belong and to Allah we return,” she says, and reaches out for Sel’s hand. Laika was one of the first rovers ever sent back to Earth, one of the first connections to a lost homeland. Most people feel that they belong here, on this world, and are simply waiting for the day they might return. Mahira isn’t so sure she belongs anywhere – but even so, she feels in awe of this place.

They’ve come here following a death, but the world is full of life, from the thick grass that their boots sink into to the birds that sing in the trees above their heads. Nature ignores disaster. Determined above all, it grows and grows, finds its roots as ivy creeps up the sides of a leaching power plant, flowers peeking out from cracks in the architecture. Ecosystems persist with a faster turnover rate.

Nothing grows on Mars; everything grows here.

Mahira could watch this new world – or old world – for hours. Once they’ve assembled a camp around their landing shuttle, she does just that, sitting on the rough earth and watching the sun set in the sky, painting it in oranges and pinks and blues and blacks. Sel brings her food and reminds her to eat, settling beside her. “This was your research, wasn’t it?” he asks, as if he didn’t read all of her work on the ship here. “The effects of radiation on terran ecosystems.”

“I didn’t think I’d ever see it up close,” she admits. Laika’s automated research has formed largely the basis of her own. She should feel sadder, but can’t find her emotions in this sea of experience. Everything is happening all at once, and she hasn’t slowed down enough for her feelings to catch up and overwhelm her. But maybe she’ll never cry for Laika at all. Doctors call it alexithymia. “I didn’t think it was going to be this... green.”

Sel laughs. “It deserves to be the Green Planet more than Mars ever deserved to be the Red one.”

“Maybe we’ll never find out what killed Laika,” she muses. “It feels like there’s so much here, and we’ve only just landed.” She’s noticed it already – the changes in birdsong, the quieting of the rustling as night sets in, the eruption of strange and uncanny cries from nocturnal animals. She prepared by listening to old clips, but the noises make gooseflesh prickle on her arms, old human instincts coming back to life. It’s easy to understand strange Earth myths now; creatures of the seas and land, crossing cultures and times, born out of strange encounters. She’s afraid but she isn’t, drawn by curiosity.

“We should do the hard bit first,” Sel suggests, talking with his mouth full. Mahira pulls a face. “Power plant first. See what’s in there, and then we can go and frolic with quadrats for the rest of the trip.”

Mahira rolls her eyes, but laughs anyway. She can’t help it. “That is not what biologists do,” she says.

“We did it in high school,” Sel says, “and I hit somebody in the face. That was the end of my biology career right there.” Even as the dark is swallowing up the finer details of his face, the important things still remain: the round flush of his cheeks, the well-worn lines around his smile. And then, finally, his face disappears into the night.

*Mahira barely sleeps. Even with earplugs in, she can hear: and instead of adjusting to the noise, she’s becoming more and more afraid. The screams feel closer, more human. They intrude into her mind with visceral images: a woman’s guts spilling out as a knife cleaves through her chest; someone who has just lost their entire family, howling despair at a cruel master; a man with his leg caught in a bear trip, incised viciously by rusty metal. When she opens her eyes, she can still feel those images clawing at the edges of her consciousness, holding onto her mind even as she begins morning prayers with the first light of dawn.

She shouts at Sel instead of eating breakfast. She shouldn’t. But she can’t help herself.

An hour later, when they’re on the outskirts of the nuclear power plant and preparing to go inside, she says she’s hungry. Her stomach hurts as it grows and contracts, and as she thinks how stupid it was to lash out, Sel presses a protein bar into her hand. “There you go,” he says.

“Oh,” she says, touched. “Thank you."

It feels strange to come upon the open door of an abandoned building; it feels as if it should be shut and padlocked, but across the overgrown town, doors and windows stay open as if the residents just disappeared. She feels her heart skip a few beats as Sel pushes open the door, which creaks and groans with the exertion, wondering what might lurk beyond; but it’s just a long expanse of dark. Sel clicks on his torch, cutting through the unknown with a beam of light, dust swirling with motion. “You didn’t sleep last night?” he asks.

“Bad dreams,” she says, a half-truth. If only she’d been asleep for them. The thoughts still hang over her like a fog.

“Me too,” he says. “I kept wishing I would wake up.”

Something scuttles in the corridor, and he starts. Mahira jumped, too, but she scolds herself.

“Probably a mouse,” she says. “Or a rat. We’re sharing the place.” Sometimes it’s easy here to forget that sounds have sources; they’re not just an ambient layer over the world, not like the earth sound files Mahira liked to listen to at home. She finishes the protein bar and retrieves her own torch. “Should we split up?”

“Nothing good has ever happened when a group splits up,” Sel points out. Mahira sighs.

“We’re not in a movie,” she says. “We could cover ground faster.”

Sel doesn’t look happy with it, but he concedes the point. Mahira reassures him that they have communication devices and trackers, so if anything does happen, she’ll be there in a matter of moments. She doesn’t like the idea of being alone with her intrusive thoughts either, but she has an unfortunate lifetime of practice, and she lets her breathing slow as she sets out in one direction. She’s canvassing the ground floor first while Sel heads for the stairs, the rickety elevator overgrown with moss and almost uncertainly untrustworthy anyway. The dust is so thick that she pauses to retrieve a face mask from her pack, tying the straps together tight at the back of her hijab.

She begins to pick her way through the rooms, through the dark. An old staff room has half-filled coffee cups with ecosystems growing on the rims; there’s a bird’s nest filled with anxious chicks in the corner of another. “Sorry,” she says on instinct. “Didn’t mean to disturb you.”

Under the mask, she’s keenly aware of her breathing, regulating it carefully; but even then, she feels that they’re coming in short. Despite herself, panic grips her chest like a vice: fear of the dark, fear of the unknown, fear of the radioactivity seeping its way through her body and poisoning her organs and the fear that the decontamination chamber in the ship is just a fiction and that she’ll die here. It overwhelms her at once, flooding her system, thought after thought after thought, tying themselves to the mast of last night. She stumbles against the wall and slips down, pulling her knees up to her chest, and activates the comms link.

“Panic attack,” she wheezes to Sel, the rational part of her mind speaking even though the rest of her is convinced that death is coming this way.

“You want me to come down or do you just wanna talk?” he asks.

“Just talk,” she says.

“I mean, this is the most rational place to have a panic attack, don’t you think? It’s dark and scary and radioactive and there are mice everywhere who seem to get their kicks from scaring me.” His voice quiets for a moment, but she can hear him moving, and then the sound of a door shutting behind him. “Oh, wow. I’ve just found the control room for the reactor. This is where it all happened, huh?” He very audibly trips over a chair, and despite herself, Mahira breaks through the feeling of hopelessness for just long enough to laugh at him. “Man, I thought the radiation was going to be the health and safety risk here, not the furniture!” More walking. “Oh, there’s a screen here, and I’m guessing that this used to be a live feed of the reactor and not so that they could watch daytime TV? Maybe I can get it back on.” She can hear what sounds like Sel simply hitting the screen. “What did you find on the ground floor?”

“Just staff rooms and break rooms. Lockers and old uniforms. It’s weird, because part of me feels like somebody is going to just walk back in, even though clearly no-one has been here for decades.”

“In my nightmare last night, I was here on my own and somebody tapped me on the shoulder and I turned around and it was this guy with his flesh literally rotting and slipping off his skeleton, and he said ‘excuse me’ and put his uniform on; and then there were dozens of them, guys with no faces just walking around me like it’s business as usual...” Sel trails off. “That was not a reassuring story at all for your panic attack. Wow. Sorry, ’hira.”

“I guess we can add rotting workers to my list of irrational fears.”

“What else is on there? Quicksand? Acid rain?”

“Anglerfish. They’re a deep sea species here, and they have this ray that emits light and hangs in front of them like a lantern, which they use to attract prey into their big, sharp teeth.”

“I feel like that’s a rational fear.”

“They’re not that big, and I wouldn’t meet one unless we went deep sea diving while we were here, which we don’t have the equipment for.”

“Yeah, but they do sound scary. Ooh, hello... I think I’ve got something here, Mahira. Maybe when you feel better, you should come up and see this.” There are a few moments where all she can hear is Sel exerting himself over something or another, and then a delighted gasp. “Yes! The screen’s on. I can see the reactor! Okay, this is in black and white for some reason – I’m guessing they were just really cheap? – but let’s see... That must be where the reactor exploded and melted down, and I can see scorch marks, but what’s that? There’s this black thing in the reactor and I’m not sure what it is. It’s really dark, like Vantablack, it doesn’t even look like it’s real. Hey, maybe we could head over to the reactor together and have a look tomorrow if we bring the protective gear... Is that moving?”

“What?”

“I think it’s moving. What the hell? Is that– is that a tentacle?”

“Sel? What are you seeing? Are you sure this is real?”

“I don’t know,” he says, and then the comms link cuts out. The hum of slight static that sat behind his voice cuts out, and when Mahira shouts his name, nothing responds. Like the satellites and the rovers, like Laika, Sel goes silent. Mahira fumbles in her pockets, pulls out the tracker, searches for the little dot that’s Sel–

There’s nothing. He’s off the radar. He’s gone.

Mahira’s chest tightens. But this time she runs, trying not to trip over anything in the cloak of darkness that envelopes the windowless power plant, desperately following the path carved out for her by the torch in her hand, following the signs up the stairs and checking room after room until finally she steps into the control room. What looks like ink has been spilled on the floor, like black blood, and she hurries over to the screen, still displaying what seems to be footage from the reactor. The current Earth time displays in the top left corner, the date on the right. Sel isn’t here, and she can’t see anything unexpected on the screen; but the ink leaves a trail, dripping across the floor like blood at a hospital.

Mahira squeezes her eyes shut, prays to Allah, prays for His light and safety, and begins to follow the trail.

Drip, drip. Drip, drip. The squeak of her shoes against the floor. Drip, drip. Drip, drip.

She wants Sel to say something funny. She wants to be back at camp. She wants to go home.

Instead, she steps out onto the walkway above the destroyed nuclear reactor, watching something of pure black crawl like an octopus across the grey metal and settle itself in the heart of the reactor, the hollowed-out explosion its nest. There is no Sel here. She wants to believe that he’s alive somewhere, but there’s a finality in the way he went silent; just stopped, like Laika, inexplicably over. The creature doesn’t seem to have eyes, but its surface is so dark that she can’t see anything, the shadow of all shadows. She can feel it watching nonetheless.

It screams inside her head.

It’s the loudest scream she’s ever heard, the scream of everything; of a reactor exploding, a body melting away with radiation sickness, the unstoppable growth of malignant tumours, organ failure, the cracking open of the earth, tornadoes and floods and fires and people fleeing their homes and finding no safe refuge, knives and bullets plunged into chests, the crying of children. Everything all at once. Everything. The scream of old Earth, the song of its destruction, a piercing cry to someone who fled it.

Mahira cannot speak. There is nothing she can say to this pain. There is nothing she can do to alleviate it. Her body goes quiet.