Hans Mueller was a man of ordinary build, intellect, expression, opinions, and features. In short, there was nothing of the extraordinary about him; he had lived all his adult life in the same street in Dresden, excluding three years at University in Aachen, and each apartment he had owned was situated within a hundred feet of the last. Childhood he had spent with two parents and one sister in a brick house near the city centre. He arose at seven each morning to work three streets away in an office building with the same floor plan as the school he had attended, took a solitary lunch at Weisswurst, and returned to his apartment by five. He was not married, and he had no children, and having lived already fifty-three years, little chance remained of either occurring in the future for him. Disregarding another habitative relocation (the last time had been due to a plumbing inconsistency), his life would continue in its steady tracks until such a day as it ended, and even then it was likely to be a standard sort of death— cardiovascular disease was the leading cause in Germany, and his diet did nothing to prevent its arrival. To alter his diet would have invited something in a very mild form of extraordinariness. The most he ever took to in that vein was a glass of prune juice.

Yet let it not be assumed that Hans supposed himself to be ordinary, in any case. It is the wont of the common man to find himself quite apart from the rest, by pure incident of his not being all that different; the bird who smooths his feathers to resemble his flock does so because he suspects that he is an outsider. Hans was so attuned to the exactitude of his life that he had come to expect he must be very different, indeed, and from this belief of his fundamental divergence came the natural expectation that he could be further attuned to the aspects of humanity he considered himself to be lacking. To begin with, he had never been more than ordinarily strong, since he did no more than the ordinary amount of exercise. He had never been more than ordinarily informed, because he read the same newspapers, and the same number of articles, as anybody else he knew. He had never been more than ordinarily attractive, because he wore the same clothes from the same shops as everybody around him, and brushed his hair for the same amount of time in the morning. It seemed to him that something external must and would arrive to better him, if he ever so desired to be bettered— so long as everybody else was being bettered, also. It would do him no good to be raised above, nor left below, for that matter.

All in all, Hans Mueller was the perfect candidate.

“Herr Mueller,” the doctor said, and held his hand out, freshly cased in latex gloves, so that when Hans shook it a residue of powder remained on his palms. He was grateful; it soaked up the nervous sweat.

Doctors had never made him nervous, but this laboratory, with its artificial lighting unbroken by a single shadow, and the percussive rhythm of machinery somewhere above them, made him want to loosen his tie. He had not known what to wear, never having been to a medical trial before, but he had decided that he would dress as he did for work, dress not to impress but to blend. And he did. The men— they were all men, roughly his age, and of a similar build— were all wearing almost the same outfit, with only colours to differentiate them; some had grey trousers, some navy, one wore black. An even divide of brogues and loafers. Hans had navy trousers, and black brogues. If it were possible to feel at home outside of his own street, he did then, in some vague knowledge that he had achieved man’s collective goal; to be very much like his fellow men.

When it appeared that the doctor was not going to make any announcement yet, but looked instead to be waiting for something, or somebody, the men arranged themselves into small concentric circles and began to shake hands and exchange their formalities; name, the street they lived on (for all were from Dresden), and profession. Walter Klein, to Hans’ left of the four-strong circle, was a stocking associate from Kirchstraße; Herbert Brandt, to Klein’s left, a line supervisor from Blumenstraße; the third, to Hans’ right, was Ernst Winkler, administrative assistant from Radeberger Straße. All of these were streets of which Hans had a pleasant knowledge, and they occupied themselves well with talk of times they had walked down each other’s streets— for example, Brandt had just the other day walked down Radeberger to meet his sister, and Hans had been on Kirchstraße a week prior, though he could not recall why.

They were all quite at a loss once these threads of conversation had snapped, none of them having ever been much obliged to talk any more than that, but the doctor was still tapping his feet and glancing towards the door, so that by-and-by their talk was dredged up once more. Since they had no more in common beyond their patterns of life, they turned to what combined them at present. Why had they come?

The general consensus seemed to be that it was something to do.

Two more men in white coats strode in, identically dressed to the doctor; Hans supposed that they must be more of the same, and was pleased to think that he was part of research which required for its course three doctors rather than just one. And with so many men around him, too, there could be no doubt that he had been selected— yes, personally selected, the letter assured, in the same typeface as his electrical bills— for something vitally important. He only hoped that his service would be of maximum use. The three doctors conferred for a few moments, and a ripple of straightened spines and shuffled shoes went about the room. The circles melded back into one cohesive unit and the subjects awaited their instructions.

“Good afternoon, gentlemen,” Verner said, and ran his sharp gaze along the gaggle of men before him, made sure to make eye contact with each one in turn. “I would like to start by saying I am very grateful to you all for partaking in our research— you are part of a very select few, handpicked by my patron.”

They all smiled in a similar fashion and he went on.

“I am Dr. Verner, and these are my colleagues, Dr. Ehrman, and Dr. Frentzel.”

The two of them nodded; Verner did not yet know which was which, having taken their names from a list handed over by his patron. They were to assist with the medical tests every morning and evening, and that was all. To ascertain which was Ehrman and which Frentzel was not in Verner’s remit.

“If you have any issues, if you need anything, please do ask my colleagues.”

He made a show of consulting his clipboard and then looked out again over the wash of ordinariness.

“Now, to the programme. You will understand why the situation has thus far entailed such secrecy— top medical science always does.” They all nodded as if they had, indeed, known all about the policies of exclusive medical explorations. “You will each receive one injection of a genetically active serum, one which will alter you both internally and externally, and make you— well, gentlemen, I do not like to use such theatrical words, but this case calls for recognition of its own grandeur. This serum will make you superhuman.”

That sent the room into a frenzy of half-raised eyebrows and small breaths expelled through thin lips. He allowed them their moment to side-eye each other, then continued;

“The serum is fast acting. It is my hope that the results will begin to manifest by the morning, and you will report to Ehrman and Frentzel any changes at all, even the most minor things. Heightened sensual capabilities, brain activity, physical strength… All of these are to be expected. And, of course, there may be some side effects, but only those which are necessary to the transformation, and they will not cause too great a distress to any of you.”

He gestured for Ehrman and Frentzel to leave for the equipment, which they did, two white-robed monks on a shared quest for enlightenment with him. Or two lackeys seeking a salary. It did not particularly matter.

“The final factor to discuss is that, since this is a venture of science, we must follow standard scientific and medical procedure with these trials, by which I mean one of you will not receive the serum.” This prompted a few less pleased reactions, but he already had their hearts, he knew. “Now, gentlemen, onto the mission itself. There are papers to be signed before the work can begin, which Ehrman and Frentzel will bring to you. I trust you will all join this voyage into the great history, and future, of science and, moreover, the advancement of the human race itself.”

With his neat signature inscribed onto thirteen forms concerning every possible aspect of the trial, Hans was directed towards a booth which had been drawn up as the men lined up to fill out the forms. It reminded him of school vaccinations, with a screen drawn up and the promise of a needle behind, his hands nervous in his pocket, and sometimes his blood a little warm when the nurse, unerringly female and soft-handed beneath her gloves, touched his bicep. He did not worry anymore over whether the muscle there was firm enough, because he could tell that it was neither more nor less firm than those of the others around him, and that was safety enough.

But this was no female nurse— Ehrman was handling the paperwork, stacking up masses of small print and surnames; Frentzel was behind the screen, calling in each subject as the last was sent to the other side of the screen. All went in with the same chiselled bravado on their jutting chin, but most so far had emerged with pursed lips and hands tellingly clenched against their sides. Hans was relieved that he could be permitted to show a little of his hurt afterwards. Being halfway or so through the alphabet, or at least in the case of names, he could watch a good few go in before himself. One of those was Klein, who stood before him in the line.

“I never liked injections,” Klein confessed to him when he was next to go, his expression the only one with genuine dread in it. Hans wanted to tell him to be quiet, that even to listen to him saying such a thing was childish; confessions required a listening ear, and that made Hans complicit in his comparative cowardice.

“I think it will be fine,” he instead replied, a trace cool in his voice. “It doesn’t seem to be taking long.”

Klein nodded and turned back to face the booth. Hans noticed a loose string on the back of his jacket and had to resist the urge to snap it off, to wrap his finger up in it and tug until he felt it break, but then Klein was called forth and the string receded to the booth. A half-minute later, Klein exited, the first on shaky legs, and just as Hans was called in he could hear Klein asking for a glass of water. He scoffed.

The needle was larger than he expected.

“Arm,” Frentzel said, and Hans removed his jacket, unbuttoned his shirt to stick forth his left arm. He wondered if he ought to have shaved his shoulder; middle age, he had found, was a hirsute time. But there was never any need— a gloved hand turned his arm to face his wrist upwards, and squeezed until a vein popped up. He averted his gaze as the needle approached the crook of his elbow, a strangely intimate place, in that it had never really been touched by anybody else before. That small and ignored piece of his body had suddenly become the site of something remarkable. The thought strengthened him when the sharp punctured his skin and he could feel it probing through each layer, searching for the vein, scraping about until… He grimaced at the sensation of the plunging liquid through his already pulsing blood. The needle was retracted, Frentzel rubbed his forearm for a few seconds, and motioned for him to leave. The next name was called.

Hans rose, finding his legs nice and steady, and joined the two faces he knew on the other side; the same factions from earlier had formed again.

Brandt and Klein watched him expectantly.

“Not so bad,” he said. “In the elbow, I wasn’t expecting that. Like doing heroin.”

They both laughed and told him they had said the exact same thing when they came out.

“Well, what’s one injection, anyway, after what Doctor Verner told us?” Brandt said. He had been the second in. “Superhuman. Wow.”

“Worth one needle,” Klein agreed.

“Poor guy who gets the placebo, though.”

“Chances are it’s one of the others.”

“Not really,” Hans said, but he was not in the mood to discuss mathematical probabilities, so he diverted course. “I wonder what we’ll do with our superhumanity when we have it. Become superheroes?”

Brandt and Klein laughed again, and Hans joined them, although he did not think what he had said was all that funny; Doctor Verner had been the one to start using the ‘super’ prefix, and they would not have laughed at him.

“I guess I’ll get a better job,” Brandt said. “With a superhuman brain, I could do all sorts of things, make more money, move out of Blumenstraße…”

Hans could not see why anybody would want to move out of Blumenstraße. It was a nice area.

“I’d start investing in the stock market,” was Klein’s proposal. “That’s where you make the real money. What about you, Mueller?”

“Oh, I don’t know. Maybe I’d try writing a book, or something, if it makes me a lot smarter. Non-fiction, probably.”

The other two nodded slowly. Winkler joined them a few minutes later, the final subject to receive the injection; not a single one had decided not to go ahead with the trial. Winkler said that he would use his superhuman abilities to go on every panel show and win as much money as he could. Hans wondered how that was any better than wanting to be a superhero. One thing they could all agree on was that they were damned hopeful they would not be the placebo.

Hans awoke in his cot bed amongst the three lines which made up the unit of subjects, all similarly tucked up with a single pillow and thin duvet. They had all been awoken at once by a sharp buzzing from above them. Understanding it to be some sort of alarm, each man stretched, yawned, and got up, put on the clothes they had been handed the evening before after a brief dinner; grey trousers, a grey cotton shirt, and grey slippers. Equality in uniformity. Something Hans had always enjoyed, something which let him relax as they all sat down for breakfast in the next room over, let him relax until he noticed that he felt the same as ever.

To wake up any other morning feeling the same as ever was usually an achievement at his age, to have no new aches, no old throbs, just a continuance of as-ever-it-was.

“My teeth are really sore,” Winkler said when he sat down.

“Mine too,” Brandt said.

“And mine,” from Klein.

They must have assumed Hans’ were the same, but he prodded them and felt nothing. Was he not supposed to be noticing symptoms by now? He saw that the others were eating nothing, and did not eat himself, though his stomach was sore from waiting— that was no symptom, though, just a body running on the cuckoo clock of its own needs.

“I slept well,” he said to make conversation.

The others looked at him, bemused.

“I had the most vivid dreams,” Brandt said. “And they were so expansive, too, I really felt like my mind was growing.”

The other two concurred. Hans pinched his lips.

“It’s okay,” Klein said to him, softly, almost under his breath, “I’m sure the symptoms will show up sooner or later. Everyone’s different.”

That was the one thing which Hans could really have done without hearing, and he spent the rest of breakfast running his tongue over his teeth.

The groups were beginning to meld together. That was the first thing Hans noticed. Those smaller fragments were joining to become one conglomerated sharing point of new symptoms; by lunch, they were losing teeth. They dropped out mid-speech, the gums around them blackened and soft, pulpy, and those calcified lumps were tossed into a growing pile before Ehrman and Frentzel. It was like some sort of initiation— lose a tooth, taste the blood against one’s tongue, spit the tooth onto the pile, and join the bigger group. Already Brandt and Winkler had moved on.

Hans did not feel even the smallest shifting of his own teeth.

“You could do it yourself,” Klein whispered to him, not yet having dropped a tooth, but displaying all likelihood of doing so within the next few minutes. He had allowed Hans to prod the softened tissue inside his mouth.

“I don’t need to,” Hans snapped.

“If you say so… At least that way you wouldn’t be on your own. You could—“ Klein paused, clamped his mouth shut, and Hans knew he had lost him.

Klein opened up his mouth to stick out his tongue, balanced upon which was a tooth down to the root, which was cracked at the tip, as if something had been pushing up into it. Hans shuddered and slipped into the bathroom.

The fluorescent light pinned him down as he stared at the fork he had brought with him; it could equally have been a knife, but he wanted something with more traction, more leverage.

He still winced these days to wipe TCP over a graze— how was he to enact such gruesome self-distortion as this? But the terror of becoming extraordinary overcame his revulsion when he envisioned the men about him growing up to supremacy, and him left behind, a dead leaf trampled into mud. He must do it.

The first prong broke skin and he groaned, but continued to press until each barb had burrowed its way through the thin layer over the bone within. He had gone for an upper canine. Eyes blinded by tears, he worked at the tooth, heard the splatter of blood into the sink, and the scrape of metal against bone, and the wet suction noise followed by a crack which made him gag. But he swallowed down the vomit, and with it a good throatful of blood, to keep from losing his prize, which he wrenched out now and held up on the fork.

When he dropped it onto the pile, Ehrman frowned, looked to Frentzel, but they said nothing, just marked something down on their clipboards. Hans joined the wider group and smiled, smiled wide enough to share in their gaps.

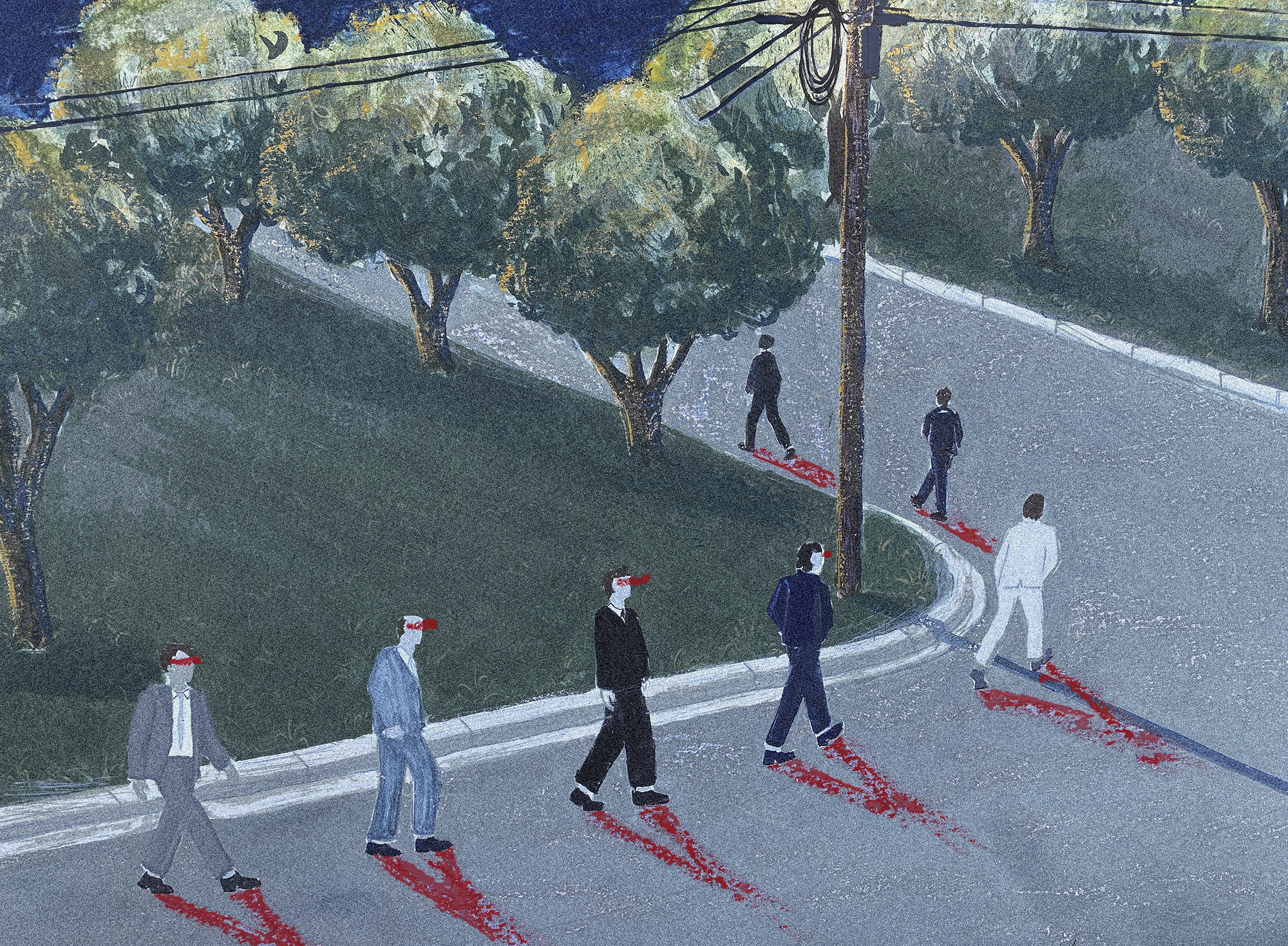

The tooth was not enough. It was not enough, and he knew it, but what more could he do? The others had started to notice that his skin remained pink, rather than following their subtle shade of grey, and that his eyes had not receded back into his head. He could not escape his humanity whilst they exceeded beyond it. There were depths he could not plumb, however desperately he wished it.

When it became apparent that he was the unchosen one, the others began to converge together, and soon he was a solitary figure, a black swan watching the white flock to migrate to kinder climate, whilst he must weather the winter alone. Their voices were low when they spoke, and they seemed to speak always from their throats now, something rasping through the sounds he heard— though he could not get close enough to discern the words themselves. He did not know if he wanted to know what they were talking about; he suspected it might be himself, since their sunken eyes would turn every so often towards him, ashen heads on drooping necks swivelling to regard him. They reminded him a little of hens losing their feathers, but he tried to remember that they were becoming above human, and he would have pulled his own feathers from the root had he had any.

And the whispers did not stop. The mumbling, murmuring, muttering; it went on at night, too. Lying in his cot, the covers pulled to his chin like a fearful child, his every sense strained towards understanding them, but he could not. Yet though he made nothing of their noise, he began to think that it was growing closer, and he perceived a softer sound beneath it, a dragging noise… And then a thump. Infant dread, at once paralytic and suffusing every muscle with charging adrenaline. He dug teeth into his tongue, curled hollow fingers about sheets, and waited. The thump came again— closer. And again, and again, and again, closer every time.

He sensed rather than saw a figure lean over him, and if his flesh could have dissolved into the mattress he would have melted away; his body did the best it could, but there was no material escape from the cold, clammy hand which closed over his mouth, the skin spongey against his clenched lips. That awful hoarse grunt from the assailant, and then the other hand fixed over his throat. Blood, useless blood, burst through Hans’ head, and his own hands struck forth, grasped at the first place they could find purpose and— fingers into an open mouth, small sharpened teeth bared ahead of a writhing tongue. Hans jerked back and scrabbled upwards, searching for those resinous eyes, but came instead against greasy hair. With his throat bulging and lungs roaring, he yanked and yanked, until the creature screeched and scurried back, retreated into the darkness. Hans sat up and went to cradle his throat, then realised he had a clump of hair still clutched in his hand, held together by a mushy glob of scalp. It was a small mercy of his situation that he fell unconscious with the revulsion.

Ehrman and Frentzel entered when the buzzer sounded the next morning. Hans immediately ran towards them, clutched at their perfectly solid skin, and pleaded with them to let him go.

“They’re monstrous,” he declared, pointing to the mass of bodies rising up from their beds, unrecognisable from the men they once had been. “They’re going to kill me. Oh God, please, they’re going to kill me!”

But they only presented him with his contract, where he had agreed to continue in the trial even if he should experience difficulty. Halfway through his entreaty, Verner entered, and took Hans aside. Never once did his eyes leave his successful subjects, and he had Ehrman and Frentzel stand between them and himself.

“Now,” he said, “what is the matter, Herr Mueller?”

“Look at them,” Hans gasped. “Surely this can’t be right? Surely this isn’t what you intended?”

Verner smiled. He still watched the room. “Herr Mueller, I agree with you that they do not look pleasant, but that is only to your simple and unadvanced eyes. They are, in fact, superior to you in every possible facet, and probably they think you very ugly now that you are the only one amongst them to look the way you do. But the truth is, this is only a transitional phase. Like the grub entering a cocoon, for some time before it becomes a butterfly, it is a mulch of organic matter. That is what you see here. The metamorphosis is not complete, that is all.”

Hans swallowed these words with relief. A transitional phase. Soon they would be comprehensible to him again, and if he could not be part of them, then at least he could know what they were.

“You are making very valuable contributions to this trial,” Verner went on. “More than you could know. Once this substrate is released, mankind will evolve to a higher form, and this could not have been done without you. As for feeling apart from the group… Well, Herr Mueller, perhaps you ought to try fitting in better.”

And then Verner patted him on the knee, and handed him something from his pocket before leaving. Hans looked down to see a scalpel.

Day could be endured, but there was no stopping the advent of night, and when the final buzzer rang, Hans did not go to his cot, but instead to crouch on the floor beside it, scalpel held out before him in a trembling hand. After his talk with Verner, he had hidden in the bathroom, into which not a soul entered but his own; what his once-fellow creatures now looked like, he could not conjecture, nor did he want to. His distance from them was an itch to him, an itch he could never manage to scratch, claw as he might at hideous pink skin which refused to loosen, and push as he might against awful protruding eyes. Until he could count himself as one of them, he could claim no safety.

Until he became. Until then. Until.

Until, and the skin, and the teeth, and the hair, and the eyes, and all… Until. Until. Nerves torn away could feel nothing. Happy whistle of metal in meat, through, under, out, off.

Peel, peel, long strips away, stringy fibres in dripping fingers, a freedom of flesh liberated from. Man, human, creature; mulch. Mulch and metamorphosis.

Press, pop, inward-looking.

Slices of man whittled off— something superior within— carving; paring; honing. Emergence.

Ordinary in extraordinary become ordinary.

Verner wrinkled his nose as a fleck of ash tumbled against his breath.

“Is that all of it?” he asked Ehrman, or Frentzel. They nodded. “Good. Good. Let’s put this mess behind us. The important question is which symptoms we’ll give the next batch… The ones we created for this round were too difficult for him to replicate, I think. It gave our little placebo no chance. Next time, next time we will get it right.”

And then he began to send the paperwork through the shredder before they could be burned atop the pile of smouldering remains. He hummed a tune as he went; Bruce Springsteen’s I’m on Fire. It had been on the radio recently.